Happy Present Meet

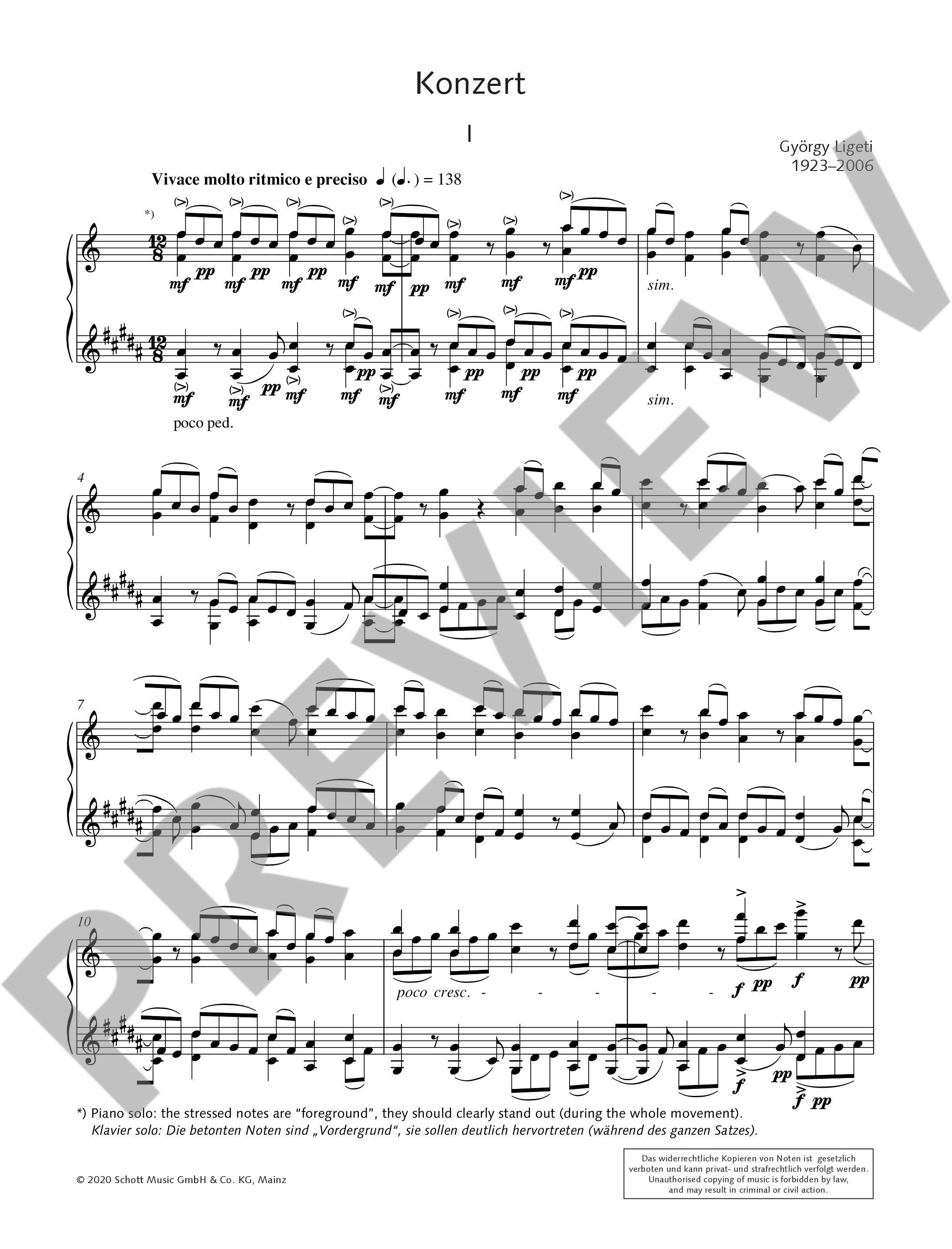

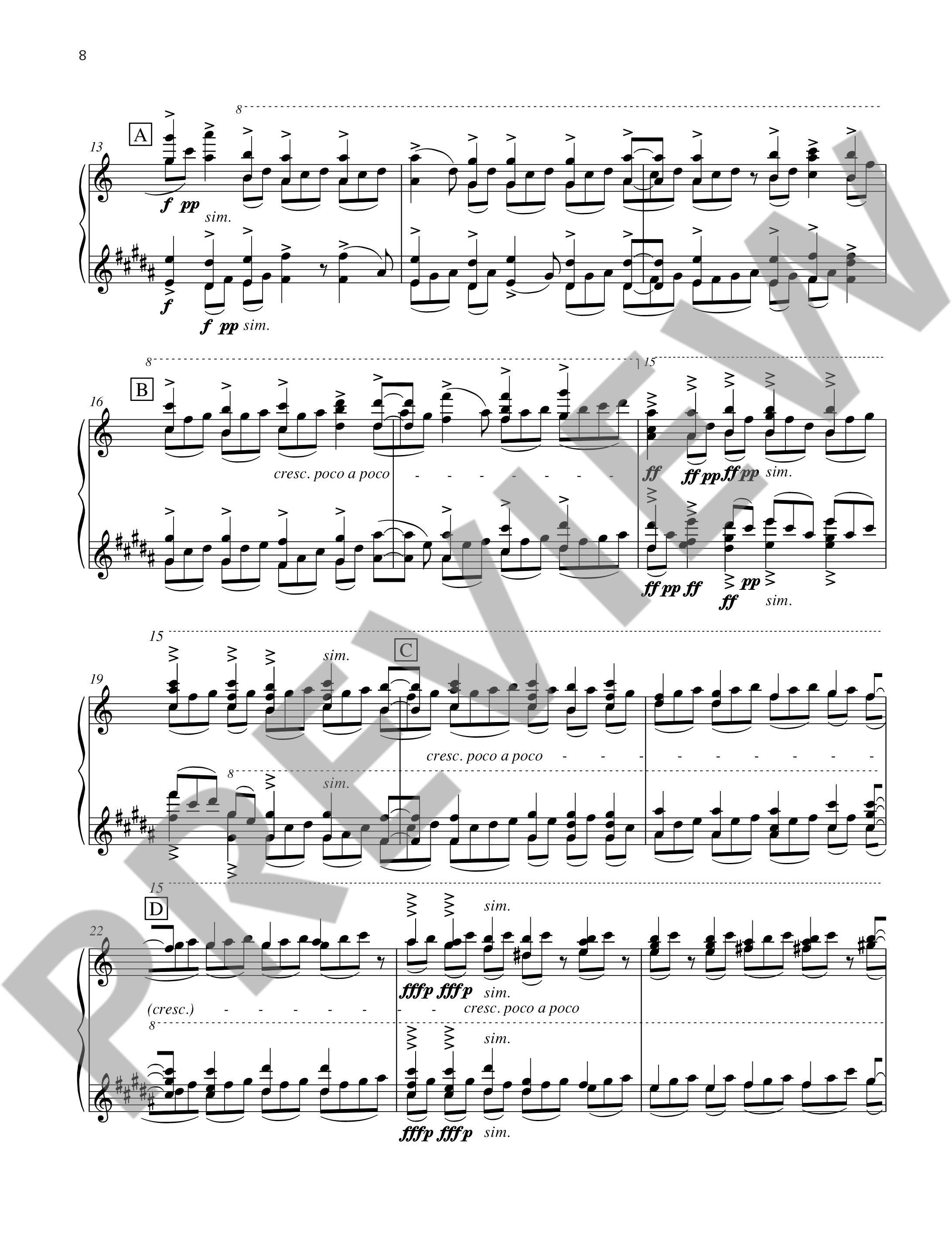

Ligeti Piano Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (Solo part only)

Difficulty: difficult

1. Vivace molto ritmico e preciso

2. Lento e deserto

3. Vivace cantabile

4. Allegro risoluto

5. Presto luminoso.

Year of composition: 1985-1988

Performance duration: 24' 0"

I composed the Piano Concerto in two stages: the first three movements during the years 1985-86, the next two in 1987, the final autograph of the last movement was ready by January, 1988. The concerto is dedicated to the American conductor Mario di Bonaventura.

The markings of the movements are the following:

1. Vivace molto ritmico e preciso

2. Lento e deserto

3. Vivace cantabile

4. Allegro risoluto

5. Presto luminoso.

The first performance of the three-movement Concerto was on October 23rd, 1986 in Graz. Mario di Bonaventura conducted while his brother, Anthony di Bonaventura, was the soloist. Two days later the performance was repeated in the Vienna Konzerthaus. After hearing the work twice, I came to the conclusion that the third movement is not an adequate finale; my feeling of form demanded continuation, a supplement. That led to the composing of the next two movements. The premiere of the whole cycle took place on February 29th, 1988, in the Vienna Konzerthaus with the same conductor and the same pianist.

The orchestra consisted of the following: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, tenor trombone, percussion and strings. The flautist also plays the piccoIo, the clarinetist, the alto ocarina. The percussion is made up of diverse instruments, which one musician-virtuoso can play. It is more practical, however, if two or three musicians share the instruments. Besides traditional instruments the percussion part calls also for two simple wind instruments: the swanee whistle and the harmonica. The string instrument parts (two violins, viola, cello and doubles bass) can be performed soloistic since they do not contain divisi. For balance, however, the ensemble playing is recommended, for example 6-8 first violins, 6-8 second, 4-6 violas, 4-6 cellos, 3-4 double basses.

In the Piano Concerto I realized new concepts of harmony and rhythm.

The first movement is entirely written in bimetry: simultaneously 12/8 and 4/4 (8/8). This relates to the known "triplet on a doule" relation and in itself is nothing new. Because, however, I articulate 12 triola and 8 duola pulses, an entangled, up till now unheard kind of polymetry is created. The rhythm is additionally complicated because of asymmetric groupings inside two speed layers, which means accents are asymmetrically distributed. These groups, as in the talea technique, have a fixed, continuously repeating rhythmic structures of varying lengths in speed layers of 12/8 and 4/4. This means that the repeating pattern in the 12/8 level and the pattern in the 4/4 level do not coincide and continuously give a kaleidoscope of renewing combinations.

In our perception we quickly resign from following particular rhythmical successions and that what is going on in time appears for us as something static, resting. This music, if it is played properly, in the right tempo and with the right accents inside particular layers, after a certain time “rises", as it were, as a plane after taking off: the rhythmic action, too complex to be able to follow in detail, begins "flying". This diffusion of individual structures into a different global structure is one of my basic compositional concepts: from the end of the fifties, from the orchestral works Apparitions and Atmosphères I continuously have been looking for new ways of resolving this basic question. The harmony of the first movement is based on mixtures, hence on the parallel leading of voices. This technique is used here in a rather simple form; later in the fourth movement it will be considerably developed.

The second movement (the only slow one amongst five movements) also has a talea type of structure, it is however much simpler rhythmically, because it contains only one speed layer. The melody is consisted in the development of a rigorous interval mode in which two minor seconds and one major second alternate therefore nine notes inside an octave. This mode is transposed into different degrees and it also determines the harmony of the movement; however, in closing episode in the piano part there is a combination of diatonics (white keys) and pentatonics (black keys) led in brilliant, sparkling quasimixtures, while the orchestra continues to play in the nine tone mode.

In this movement I used isolated sounds and extreme registers (piccolo in a very low register, bassoon in a very high register, canons played by the swanee whistle, the alto ocarina and brass with a "harmon-mute"' damper, "cutting" sound combinations of the piccolo, clarinet and oboe in an extremely high register, also alternating of a whistle-siren and xylophone). The third movement also has one speed layer and because of this it appears as simpler than the first, but actually the rhythm is very complicated in a different way here. Above the uninterrupted, fast and regular basic pulse, thanks to the asymmetric distribution of accents, different types of hemiolas and "inherent melodical patterns" appear (the term was coined by Gerhard Kubik in relation to central African music). If this movement is played with the adequate speed and with very clear accentuation, illusory rhythmic-melodical figures appear. These figures are not played directly; they do not appear in the score, but exist only in our perception as a result of co-operation of different voices.

Already earlier I had experimented with illusory rhythmics, namely in Poème symphonique for 100 metronomes (1962), in Continuum for harpsichord (1968), in Monument for two pianos (1976), and especially in the first and sixth piano etude Désordre and Automne à Varsovie (1985).

The third movement of the Piano Concerto is up to now the clearest example of illusory rhythmics and illusory melody. In intervallic and chordal structure this movement is based on alternation, and also inter-relation of various modal and quasi-equidistant harmony spaces. The tempered twelve-part division of the octave allows for diatonical and other modal interval successions, which are not equidistant, but are based on the alternation of major and minor seconds in different groups. The tempered system also allows for the use of the anhemitonic pentatonic scale (the black keys of the piano). From equidistant scales, therefore interval formations which are based on the division of an octave in equal distances, the twelve-tone tempered system allows only chromatics (only minor seconds) and the six-tone scale (the whole-tone: only major seconds).

Moreover, the division of the octave into four parts only minor thirds) and three parts (three major thirds) is possible. In several music cultures different equidistant divisions of an octave are accepted, for example, in the Javanese slendro into five parts, in Melanesia into seven parts, popular also in southeastern Asia, and apart from this, in southern Africa. This does not mean an exact equidistance: there is a certain tolerance for the inaccurateness of the interval tuning.

These exotic for us, Europeans, harmony and melody have attracted me for several years. However I did not want to re-tune the piano (microtone deviations appear in the concerto only in a few places in the horn and trombone parts led in natural tones). After the period of experimenting, I got to pseudo- or quasiequidistant intervals, which is neither whole-tone nor chromatic: in the twelve-tone system, two whole-tone scales are possible, shifted a minor second apart from each other. Therefore, I connect these two scales (or sound resources), and for example, places occur where the melodies and figurations in the piano part are created from both whole tone scales; in one band one six-tone sound resource is utilized, and in the other hand, the complementary. In this way whole-tonality and chromaticism mutually reduce themselves: a type of deformed equidistancism is formed, strangely brilliant and at the same time "slanting"; illusory harmony, indeed being created inside the tempered twelve-tone system, but in sound quality not belonging to it anymore.

The appearance of such "slantedequidistant harmony fields" alternating with modal fields and based on chords built on fifths (mainly in the piano part), complemented with mixtures built on fifths in the orchestra, gives this movement an individual, soft-metallic colour (a metallic sound resulting from harmonics).

The fourth movement was meant to be the central movement of the Concerto. Its melodc-rhythmic elements (embryos or fragments of motives) in themselves are simple. The movement also begins simply, with a succession of overlapping of these elements in the mixture type structures. Also here a kaleidoscope is created, due to a limited number of these elements - of these pebbles in the kaleidoscope - which continuously return in augmentations and diminutions.

Step by step, however, so that in the beginning we cannot hear it, a compiled rhythmic organization of the talea type gradually comes into daylight, based on the simultaneity of two mutually shifted to each other speed layers (also triplet and duoles, however, with different asymmetric structures than in the first movement). While longer rests are gradually filled in with motive fragments, we slowly come to the conclusion that we have found ourselves inside a rhythmic-melodical whirl: without change in tempo, only through increasing the density of the musical events, a rotation is created in the stream of successive and compiled, augmented and diminished motive fragments, and increasing the density suggests acceleration.

Thanks to the periodical structure of the composition, "always new but however of the same" (all the motivic cells are similar to earlier ones but none of them are exactly repeated; the general structure is therefore self-similar), an impression is created of a gigantic, indissoluble network. Also, rhythmic structures at first hidden gradually begin to emerge, two independent speed layers with their various internal accentuations.

This great, self-similar whirl in a very indirect way relates to musical associations, which came to my mind while watching the graphic projection of the mathematical sets of Julia and of Mandelbrot made with the help of a computer. I saw these wonderful pictures of fractal creations, made by scientists from Brema, Peitgen and Richter, for the first time in 1984. From that time they have played a great role in my musical concepts. This does not mean, however, that composing the fourth movement I used mathematical methods or iterative calculus; indeed, I did use constructions which, however, are not based on mathematical thinking, but are rather "craftman’s" constructions (in this respect, my attitude towards mathematics is similar to that of the graphic artist Maurits Escher). I am concerned rather with intuitional, poetic, synesthetic correspondence, not on the scientific, but on the poetic level of thinking.

The fifth, very short Presto movement is harmonically very simple, but all the more complicated in its rhythmic structure: it is based on the further development of ''inherent patterns" of the third movement. The quasi-equidistance system dominates harmonically and melodically in this movement, as in the third, alternating with harmonic fields, which are based on the division of the chromatic whole into diatonics and anhemitonic pentatonics. Polyrhythms and harmonic mixtures reach their greatest density, and at the same time this movement is strikingly light, enlightened with very bright colours: at first it seems chaotic, but after listening to it for a few times it is easy to grasp its content: many autonomous but self-similar figures which crossing themselves.

I present my artistic credo in the Piano Concerto: I demonstrate my independence from criteria of the traditional avantgarde, as well as the fashionable postmodernism. Musical illusions which I consider to be also so important are not a goal in itself for me, but a foundation for my aesthetical attitude. I prefer musical forms which have a more object-like than processual character. Music as "frozen" time, as an object in imaginary space evoked by music in our imagination, as a creation which really develops in time, but in imagination it exists simultaneously in all its moments. The spell of time, the enduring its passing by, closing it in a moment of the present is my main intention as a composer.

(György Ligeti)

나는 피아노 협주곡을 두 단계로 나누어 작곡했습니다. 처음 세 악장은 1985~86년에, 다음 두 악장은 1987년에 완성되었습니다. 마지막 악장의 최종 사인은 1988년 1월에 준비되었습니다. 이 협주곡은 미국 지휘자 마리오 디에게 헌정되었습니다. 보나벤투라.

무브먼트의 표시는 다음과 같습니다.

1. Vivace molto ritmico e preciso

2. 렌토 에 데세토

3. 비바체 칸타빌레

4. 알레그로 리솔루토

5. 프레스토 루미노소.

3악장 협주곡의 첫 공연은 1986년 10월 23일 그라츠에서 열렸습니다. 마리오 디 보나벤투라는 그의 형인 안토니 디 보나벤투라가 솔리스트로 활동하는 동안 지휘를 맡았습니다. 이틀 후 비엔나 콘체르트하우스에서 공연이 반복되었습니다. 작품을 두 번 들은 후 나는 세 번째 악장이 적절한 피날레가 아니라는 결론에 도달했습니다. 나의 형태에 대한 느낌은 계속과 보충을 요구했습니다. 이것이 다음 두 악장의 작곡으로 이어졌습니다. 전곡의 초연은 1988년 2월 29일 비엔나 콘체르트하우스에서 같은 지휘자와 같은 피아니스트가 함께 열렸습니다.

오케스트라는 플루트, 오보에, 클라리넷, 바순, 호른, 트럼펫, 테너 트롬본, 타악기 및 현악기로 구성되었습니다. 플루트 연주자는 피콜로, 클라리넷 연주자, 알토 오카리나도 연주합니다. 타악기는 다양한 악기로 구성되어 있어 한 명의 음악가-거장이 연주할 수 있습니다. 그러나 두세 명의 연주자가 악기를 공유하는 것이 더 실용적입니다. 전통 악기 외에도 타악기 부분에는 스와니 휘슬과 하모니카라는 두 가지 간단한 관악기도 필요합니다. 현악기 파트(바이올린 2개, 비올라, 첼로, 더블베이스)는 디비시(divisi)가 포함되어 있지 않기 때문에 독주로 연주할 수 있습니다. 그러나 균형을 위해서는 제1바이올린 6~8대, 제2바이올린 6~8대, 비올라 4~6대, 첼로 4~6대, 더블베이스 3~4대 등 합주 연주를 권장합니다.

피아노 협주곡에서 나는 화성과 리듬의 새로운 개념을 깨달았습니다.

첫 번째 악장은 전적으로 바이메트리로 작성되었습니다(동시에 12/8 및 4/4(8/8)). 이는 알려진 "삼중항" 관계와 관련이 있으며 그 자체로는 새로운 것이 아닙니다. 그러나 나는 12개의 트리올라 펄스와 8개의 듀올라 펄스를 연결하기 때문에 지금까지 들어본 적이 없는 얽힌 폴리메트리가 생성됩니다. 두 개의 속도 레이어 내부의 비대칭 그룹화로 인해 리듬이 추가로 복잡해지며, 이는 악센트가 비대칭적으로 분포됨을 의미합니다. 탈레아 기법과 마찬가지로 이러한 그룹은 12/8 및 4/4의 속도 레이어에서 다양한 길이의 고정되고 연속적으로 반복되는 리듬 구조를 가지고 있습니다. 이는 12/8 레벨의 반복 패턴과 4/4 레벨의 패턴이 일치하지 않고 지속적으로 갱신되는 조합의 만화경을 제공한다는 것을 의미합니다.

우리의 인식에서 우리는 특정 리듬의 연속을 따르는 것을 빨리 포기하고 시간에 따라 일어나는 일이 우리에게 정적이고 쉬고 있는 것으로 나타난다는 것을 인식합니다. 이 음악은 적절한 템포와 특정 레이어 내부의 올바른 액센트로 적절하게 연주되면 일정 시간이 지나면 마치 이륙 후 비행기처럼 "상승"합니다. 리드미컬한 액션이 너무 복잡해서 불가능합니다. 세부적으로 따라가면 "비행"이 시작됩니다. 개별 구조를 다른 글로벌 구조로 확산시키는 것은 나의 기본 작곡 개념 중 하나입니다. 50년대 말부터 오케스트라 작품 Apparitions 및 Atmosphères에서 저는 계속해서 새로운 방식을 찾고 있었습니다. 이 기본적인 문제를 해결하기 위해 첫 번째 악장의 화성은 혼합을 기반으로 하므로 성부의 평행 진행에 기초합니다. 이 기술은 여기서는 다소 단순한 형태로 사용되지만 나중에 네 번째 악장에서는 상당히 발전할 것입니다.

두 번째 악장(다섯 악장 중 유일한 느린 악장) 역시 탈레아 유형의 구조를 가지고 있지만 속도 레이어가 하나만 포함되어 있기 때문에 리드미컬하게 훨씬 단순합니다. 멜로디는 2개의 단초와 1개의 장초가 교대로 나타나는 엄격한 간격 모드의 개발로 구성되어 있으므로 한 옥타브 내에 9개의 음이 있습니다. 이 모드는 다양한 각도로 변형되며 무브먼트의 조화를 결정하기도 합니다. 그러나 피아노 부분의 마지막 에피소드에는 화려하고 반짝이는 준혼합물에서 이어지는 온음계(흰 건반)와 펜타토닉(검은 건반)의 조합이 있으며 오케스트라는 계속해서 9음 모드로 연주합니다.

이 악장에서 나는 고립된 소리와 극한 음역을 사용했습니다(매우 낮은 음역의 피콜로, 매우 높은 음역의 바순, 스와니 휘슬이 연주하는 대포, 알토 오카리나 및 "하모 뮤트" 댐퍼, "커팅"이 있는 금관) 매우 높은 음역에서 피콜로, 클라리넷, 오보에의 사운드 조합, 휘파람 사이렌과 실로폰이 번갈아 가며 나타납니다. 세 번째 악장 역시 하나의 속도 레이어를 갖고 있기 때문에 첫 번째 악장에 비해 단순해 보이지만 사실 여기서는 리듬이 다른 방식으로 매우 복잡합니다. 중단되지 않고 빠르고 규칙적인 기본 맥박 위에는 악센트의 비대칭 분포 덕분에 다양한 유형의 헤미올라와 "고유의 멜로디 패턴"이 나타납니다(이 용어는 Ge에 의해 만들어졌습니다).

작곡가 Ligeti, Gyeorgy (1923- )